Information Architecture: The Skill That Separates Good Designers from Great Ones

A client sends you their content: 47 pages of Google Docs, a folder of images, a list of twelve services, four team members, six case studies, a blog with 80 posts, and the instruction :make it look good."

You open Squarespace.

You stare at the blank editor.

And the question that determines whether the finished site will actually work for visitors has nothing to do with fonts, colours, or layouts. The question is: how should this content be organised?

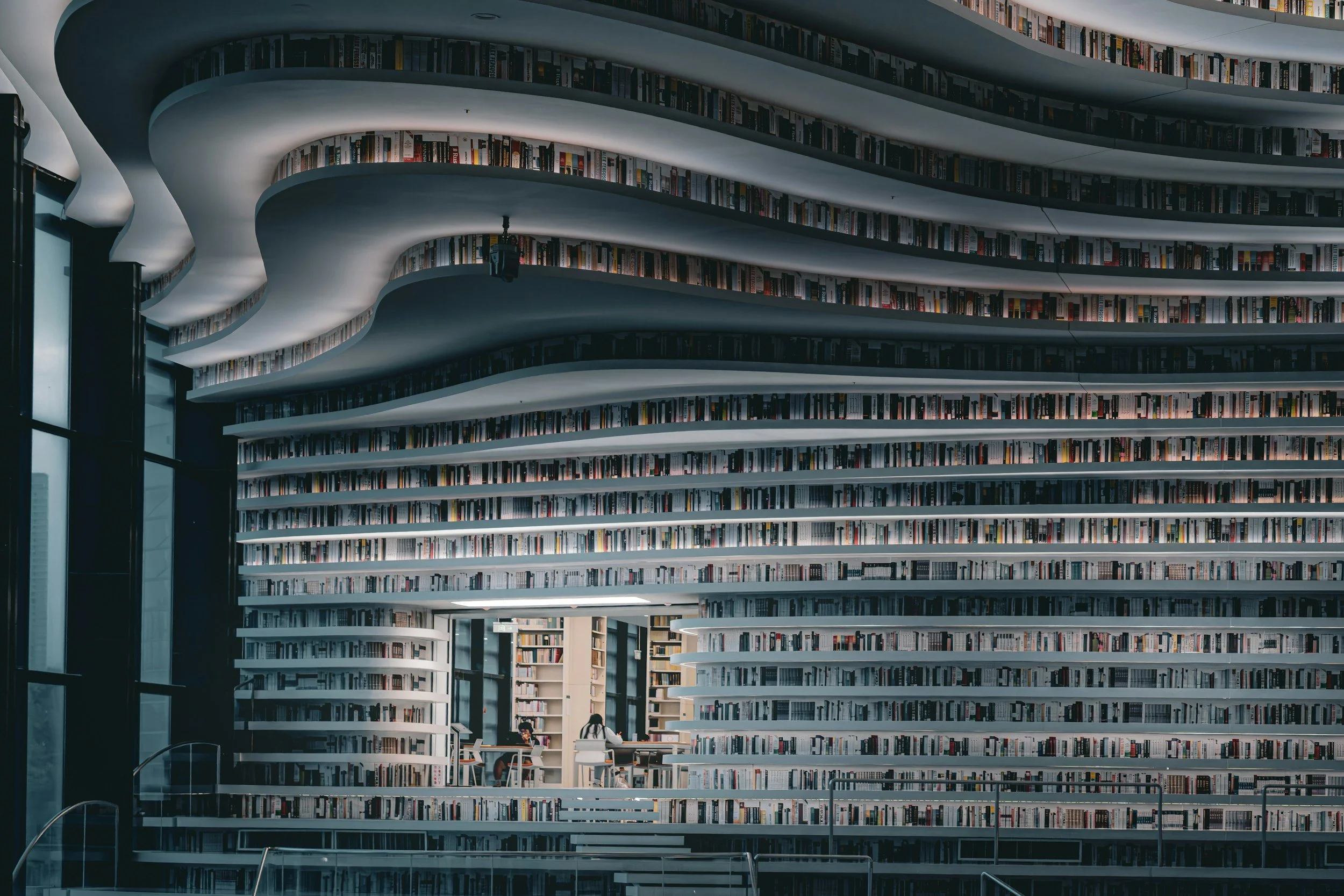

Information architecture (IA) is the practice of structuring and labelling content so that people can find what they need and understand what they've found. It's the skeleton of a website, the thing that everything else hangs on. And it's the area where the gap between “designer who makes things look nice" and “designer who builds things that convert" is widest.

Why IA Matters More Than Visual Design

Here's a claim that might sting: a website with excellent information architecture and mediocre visual design will outperform a website with excellent visual design and mediocre information architecture, every single time.

The reason is simple. Visual design affects how a website feels. Information architecture affects whether a website works. A visitor can forgive a slightly dated font or a less-than-perfect colour palette. They will not forgive not being able to find the information they came for. And when they can't find it, they leave. They don't send you feedback. They don't try harder. They just leave, and you never know it happened because the only trace is a bounce rate percentage that's higher than it should be.

Studies consistently show that the majority of users who can't find what they're looking for on a website within the first few seconds will leave without trying the navigation. They won't search. They won't scroll. They'll go back to Google and click the next result. Your information architecture is the thing that determines whether those first seconds are productive or wasted.

The Four Systems of Information Architecture

Rosenfeld and Morville's foundational IA framework identifies four interconnected systems that, together, determine how well a website's content is structured.

Organisation systems define how content is grouped. The most common approaches are topical (grouped by subject: “Services," “About," “Blog"), audience-based (grouped by who it's for: “For Homeowners," “For Businesses"), task-based (grouped by what the visitor wants to do: “Book a Session," “Learn More," “Get a Quote"), and chronological (grouped by time: blog archives, event listings). Most websites use a combination, with topical organisation as the primary structure and task-based elements as secondary navigation (CTAs, quick links).

Labelling systems determine what you call things. The words you use in navigation, headings, and links are the primary way visitors understand what's behind them. A link labelled “Solutions" means nothing. A link labelled “Kitchen Renovations" means everything. The best labels are the words your visitors would use to describe what they're looking for, which is often different from the words the business uses internally. A law firm might call their work “dispute resolution services." Their clients are googling “help with a contract disagreement." The label should match the client's language, not the firm's.

Navigation systems provide the mechanisms for moving through content. These include global navigation (the main menu, present on every page), local navigation (sub-navigation within a section), contextual navigation (inline links within content that connect related pages), and supplementary navigation (sitemaps, search, breadcrumbs). Each serves a different purpose, and a well-architected site uses all of them deliberately.

Search systems provide an alternative to navigation for visitors who know what they're looking for but not where it lives. Squarespace includes a built-in search function that can be added to the header. For content-heavy sites (large blogs, extensive product catalogues, resource libraries), search isn't optional. It's essential. But search should complement good navigation, not compensate for poor navigation.

Navigation Depth vs. Breadth

One of the most common IA decisions in Squarespace design is how to structure the main navigation. The choice is between breadth (many items in the top-level menu) and depth (fewer top-level items with dropdown submenus).

Research on navigation usability is clear: broader, shallower navigation is almost always better than narrow, deep navigation. A top-level menu with seven items is easier to scan and understand than a menu with three items, each containing nested dropdowns with ten sub-items. Every click deeper into a navigation hierarchy increases the chance that a visitor will lose their orientation and give up.

The practical guideline is to keep your primary navigation to five to seven items, each clearly labelled with the visitor's language. If a section has sub-pages, use a dropdown, but keep dropdowns to a single level (no nested dropdowns within dropdowns). If you can't fit your content into this structure, the problem isn't the navigation. It's the content organisation. You have too many categories at the wrong level of granularity, and the fix is to restructure the content, not to add more navigation layers.

In Squarespace 7.1, the header navigation supports dropdowns with the folder feature (pages grouped into a folder appear as a dropdown in the menu). The platform doesn't support mega-menus natively (large multi-column dropdowns), though these can be built with custom code. In most cases, if you need a mega-menu, your site's IA needs rethinking more than your navigation needs expanding.

The Homepage as a Routing System

Most clients think of their homepage as a showcase. It should "look impressive" and "show everything we do." The instinct is to cram the homepage with content: every service, every testimonial, every team member, every recent blog post.

Better to think of the homepage as an airport terminal. Its job is not to display every destination. Its job is to route visitors to the right gate as quickly as possible. Most homepage visitors fall into one of three to five categories, and the homepage should identify those categories and provide clear paths to the content each one needs.

A therapist's homepage, for example, might serve three types of visitors: people looking for a specific type of therapy (route to services page), people checking whether this therapist feels like the right fit (route to about page), and people ready to book (route to booking page). The homepage should address all three within the first viewport, with clear, distinct pathways for each.

This means the homepage content should be organised by visitor intent, not by content type. Instead of “About Us section, Services section, Testimonials section, Blog section" (content-type organisation), think “What we do and who we help, Why clients choose us, How to get started" (intent-based organisation). The same content appears, but it's structured around what visitors need rather than what the business wants to show.

Content Hierarchy Within Pages

IA isn't just about site-level structure. It operates within individual pages too, determining the order in which information is presented and the visual weight given to each element.

The principle of progressive disclosure is useful here: present the most important information first, and reveal detail progressively as the visitor scrolls or clicks. A services page shouldn't open with a 300-word paragraph about the company's philosophy. It should open with a clear statement of what the service is and who it's for, followed by key benefits, then details, then social proof, then a call to action.

This order isn't arbitrary. It follows the visitor's natural decision process:

“Is this what I'm looking for?" (relevance),

"Is this any good?" (evaluation),

“What exactly is involved?" (detail),

“Can I trust this?" (proof),

“What do I do next?" (action).

Structuring content in this order means the visitor gets the information they need at each stage of their decision, in the order they need it.

In Squarespace's Fluid Engine, this translates to section order and content priority within each section. The most important content should be in the first section, with the most important element in the most visually prominent position within that section. Subsequent sections should follow the progressive disclosure order. If a visitor never scrolls past the third section, they should have already understood what the page is about, why it matters, and how to take action.

Card Sorting: The IA Tool You Should Be Using

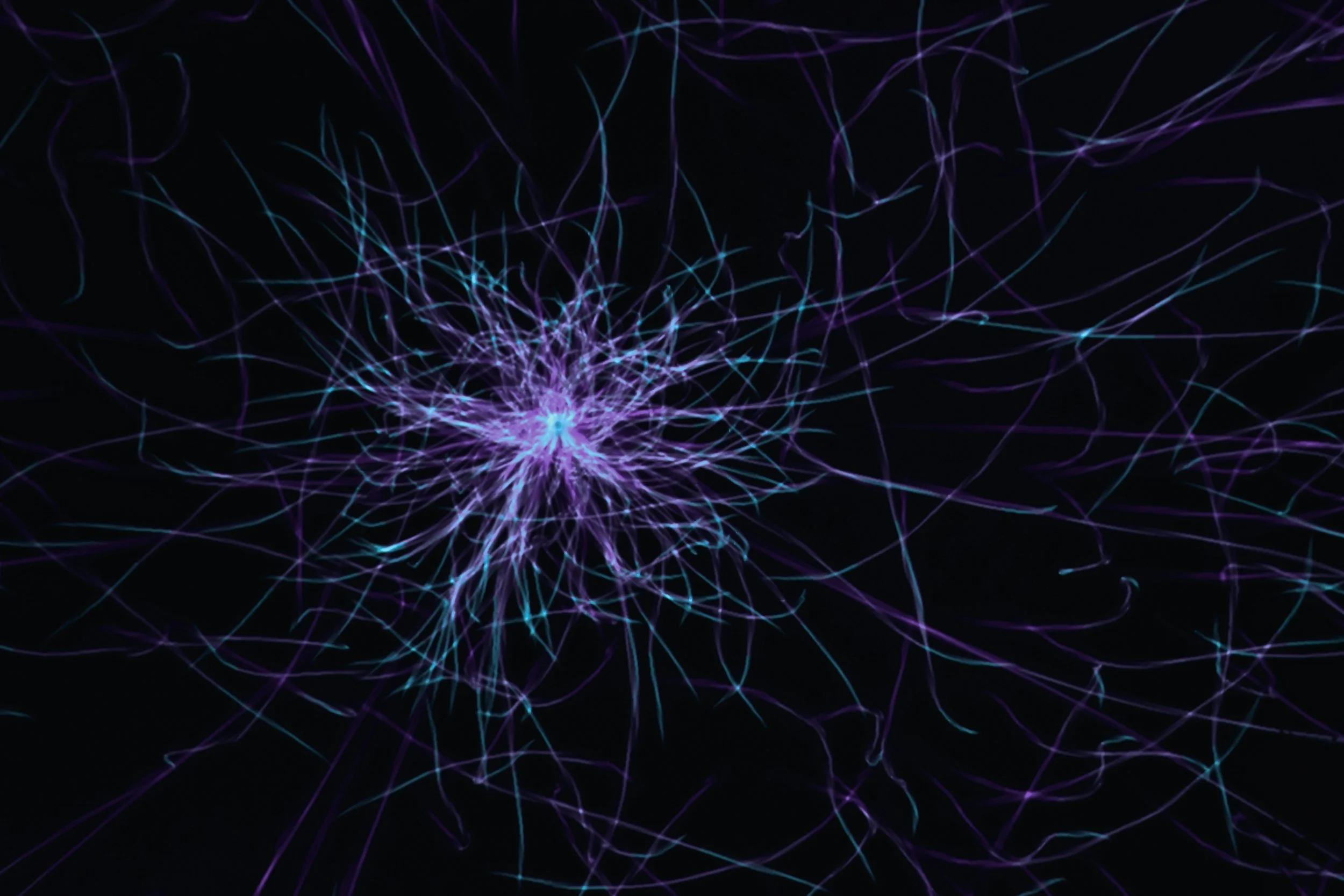

Card sorting is a user research technique where you write each piece of content on an index card and ask representative users to group the cards into categories that make sense to them. It's the single most effective way to discover how your client's audience thinks about the content, which is almost always different from how the business thinks about it.

In a physical card sort, you write each page or content item on a separate card: “Individual Therapy," “Couples Therapy," “CBT," “EMDR," “About Dr. Smith," “Fees," “Contact," “Blog," “FAQs," “Insurance Information," and so on. You give the stack to five to eight people who match the client's target audience and ask them to group the cards into piles and name each pile. The groupings and names they choose become your navigation structure.

You can do card sorting digitally using tools like Optimal Workshop or even a simple spreadsheet shared with a few of the client's existing clients. The investment is minimal (an hour or two) and the insight is invaluable, because it replaces the guesswork of “how should this be organised?" with actual data about how the target audience organises information mentally.

Most designers skip this step because it feels like research rather than design. But the navigation structure you build from a card sort will be fundamentally more usable than one you create based on the client's internal business structure or your own assumptions, and the difference will show up in lower bounce rates, longer session durations, and higher conversion rates.

Common IA Mistakes in Squarespace Sites

Organising by business structure rather than user needs. A company with three departments creates three navigation sections matching those departments. The visitor doesn't know or care about the internal org chart. They care about what they need.

Using vague labels. “Solutions," “Resources," “What We Do." These labels require the visitor to click to find out what's behind them, which is friction. Specific labels (“Kitchen Design," “Pricing," “Free Guides") tell the visitor what's behind the link before they click.

Too many pages, too few pathways. A site with 30 pages but no clear user flow is a maze. Every page should have an obvious “next step" that moves the visitor closer to a goal (contacting, booking, buying, subscribing). If a page is a dead end with no onward path, it's either incomplete or unnecessary.

Ignoring the blog as a structural element. Blog categories in Squarespace function as a secondary navigation system. Well-chosen categories (matching the terms visitors search for) make blog content discoverable. Default or absent categories make blog content invisible once it scrolls off the first page.

Duplicating content across pages. If the same information appears on multiple pages, visitors lose trust in the navigation. They don't know which version is current, and they lose confidence that they've found the right place. Each piece of information should live in one place, with links pointing to it from other relevant pages.

Information architecture is invisible when it's done well. The visitor finds what they need, takes the action they came to take, and leaves with a positive impression of the business. They don't think “what great information architecture." They think “that was easy." Making things feel easy is the hardest and most valuable thing a designer can do.

Related Articles